Notes on Kant's Prolegomena, Part III

Narcissism, scientific culture, and transcendental heroism

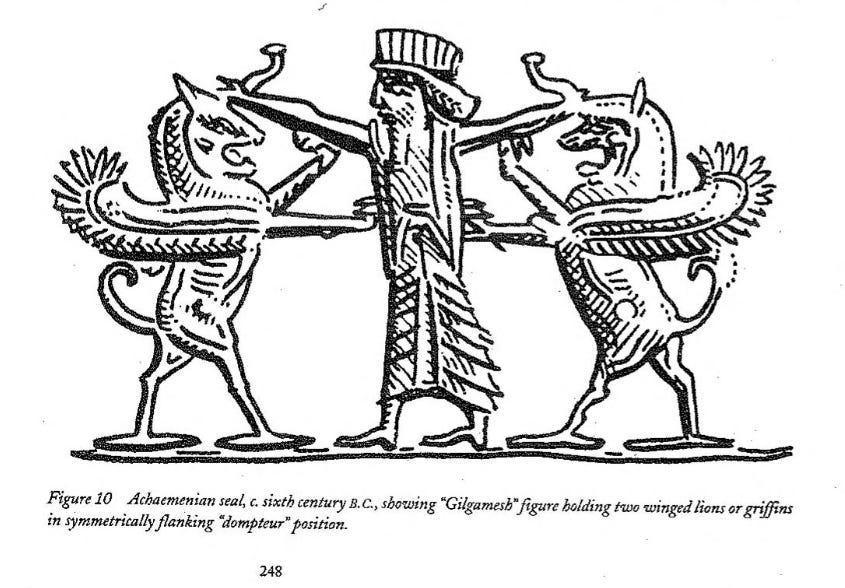

An unknown Minoan goddess

*

—Summary of insights, aka tl;dr:

Intellect can be meaningfully considered a “subject”, when this latter term is taken in its barest and most generic sense.

Where intellect perceives a field of intelligible potencies, the transcendental subject sees only a narrow link of causes and effects.

For a transcendental age, Narcissus and Prometheus are the only real alternatives.

Transcendentality is a “realm” of pure mediation, of the mediate mediating the mediate.

The condition of the synthetic a priori’s possibility is an intellective synthesis.

Intellection is the condition of the transcendental subject’s possibility, and the transcendental subject is the condition of the impossibility of the suture of the two intellects.

“Things in themselves” means “things as they are in themselves”—which is to say, it is being, or intellection, which is implied in this concept.

Discursive concepts are “transcendental reductions” of intelligible symbols.

Transcendental subjectivity renders unknown that which is most knowable, that which is as that which it is not. In this capacity, it displays its “heroic power”.

*

“...some ground of cognition a priori which lies deeply hidden but which might reveal itself by these its effects”

(23)

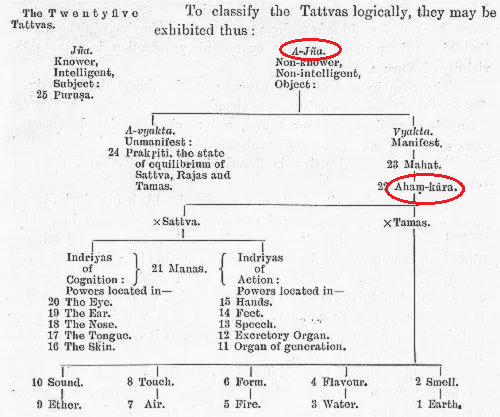

From the standpoint of a “vertical” causation [1], the synthetic a priori precisely lies in the domain of effects and not of fundamental causes. So, the “deeply hidden” source which Kant is searching for (implicitly searching for, as it were) is really intellection, that same “intellectual intuition” which he excludes from his thinking. Of course, from another standpoint, the transcendental subject has a certain priority over intellection, though this priority is not exactly “causal” except perhaps in the sense of an “action at a distance” (a kind of “wu wei”). The transcendental subject, being a sort of nothing, stands in direct analogy with other nothings, such as Neoplatonic “Matter”, or Plato's unintelligible (or supra-intelligible) Form of the Good. This analogy between sorts of no-thing, specifically the analogy between prima materia and non-being, is dealt with by Guenon in an essay from the collection titled Initiation and Spiritual Realization, and is referred to by Proclus, in his Theology of Plato, as a “dissimilar similarity”, a potent expression that could almost serve as a substitute for my “generic ambiguity” (almost). The transcendental subject also has an analogy with the two intellects [2] (this should come as no surprise—it is, after all, a kind of imitation of them). We might consider Dasein, for instance, with reference to the generic ambiguity of “subjectivity”—Dasein is not a “subject” but rather passive intellection, and yet we may meaningfully speak of it “as if” it were a subject. This is simply to say that Dasein is a sort of subject, that we speak of it and conceptualize it as a sort of subject, though a subject not limited by mere subjectivity (that is, Dasein is intellective, and hence beyond the subject-object dichotomy—it is a “subject” beyond subjectivity). Which is also to say, “subjectivity” (and by the same token, objectivity), at its most generic, is ambiguous enough to “drive both ways”, towards transcendentality and transcendence, but it eminently and properly belongs only to the transcendental. Naturally, this is both contradictory and impossible, but transcendentality is always impossible, and generic ambiguity itself, too, is eminently and properly transcendental even if it “drives both ways”, toward the transcendent—it is transcendentality itself which “drives both ways”. In that regard, the Atman of advaita vedanta is the analogue of the transcendental subject from the side of active intellection (that is, Atman, though beyond the subject-object dichotomy, is also conceptualized as a sort of “transubjective subject”, as “the witness”). So, it is precisely from the standpoints of passive and active intellection (the one “horizontal”, the other “vertical”, to frame them symbolically) that the transcendental subject appears causally posterior—this is how Hermes, the “mere messenger”, deceives us. From the standpoint of passive intellection, the transcendental subject appears to emerge from out of our being-in-the-world as from out of its horizontal “ground”, like a shoot sprouting out of the earth—that is, being-in-the-world, or Dasein, appears to be more basic than, and prior to, transcendental subjectivity, and indeed to be its parent, birthing it out of the bewilderment of vorhandenheit. From the vertical standpoint of active intellection, the transcendental subject appears to “descend” analytically from out of the sundering of intelligible wholes as ahaṁkāra (“automorphosis”), part of the lower range of descending “tattvas” (though, in a way, at the beginning of the whole series as “avidyā” [3], without which no “descent” would occur).

The twenty-five tattvas of Samkhya, with ajñāna (= avidyā) and ahaṁkāra circled in red

There is also an important aspect here of “diversity of possibilities” [4]. The derivation through analysis (though, not necessarily analytic judgment), out of intelligible wholes, whether those wholes are taken from the standpoint of passive intellection (e.g. the “work environment”, the “world” in the sense of being-in-the-world) or active intellection (e.g. Platonic forms), is a process which can proceed indefinitely (in any given “direction”) and in an indefinite multitude of ways (from any given “starting point”). For instance, consider the multitude of standpoints one finds in “metaphysical Tradition” vis a vis the nature of transcendental subjectivity—e.g. the various interpretations of maya present in the Hindu tradition, the Kabbalistic notion of tzimtzum, the Catholic conception of the subject as the contingent beneficiary of divine grace, etc etc. Likewise, an indefinite multitude of possibilities of derivation should also be possible from the standpoint of passive intellection (the aforementioned possibilities primarily adopt the standpoint of “metaphysical Tradition”, i.e. slanted toward active intellection).

1: Which is to say, in terms of atemporal dependencies. Intellection and the transcendental subject are two kinds of timelessness, and may be found in two kinds of time—two kinds of timelessness in time. Intellective time (e.g. “ecstatic temporality”), a kind of intelligible continuity, is not transcendental time. Neither is the abstract timelessness of the transcendental subject's categories the same as the “eternal presence” of intellect. And yet, both are meaningfully confounded in the generic ambiguity of “timelessness” and “time”.

2: In this connection, it should be recalled that analogy itself, in its most genuine sense, is something intellective. The transcendental subject extends itself in dependency on intellect—which is also to say, it takes intellect as a source of power, grasps it as a technology.

3: Which is to say, ahaṁkāra is but applied avidyā, avidyā in action, specifying itself here and there, in this or that form.

4: Actually, strictly speaking, we might speak of a “diversity of potencies” (see my notes on Aristotle's De Anima). These potencies are intrinsic to the whole situation of the transcendental subject in its sojourn through intelligibility. The transcendental subject is a crouching tiger in the jungle of intelligibility, ready to leap here and there, or to slink away. It is only intellect that sees the expanse of these potencies. The transcendental subject, on its own, always views itself rather narrowly, not in terms of the intelligible expanse of potency but in terms of the inevitability of causes and effects, in their most skeletal sense.

*

“...intuition contains nothing but the form of sensibility, which in me as subject precedes all the actual impressions”

(24)

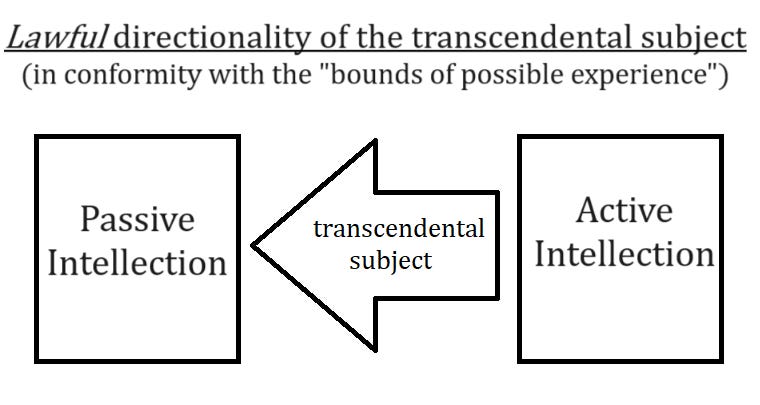

Kant's usage of “intuition” here might lend itself to some confusions for us if we do not apply some careful distinctions in the possible meanings of this term, that is, particularly, if we do not take into account its generic ambiguity or, in Proclean terms, the “dissimilar similarity” of the transcendent and the transcendental. What has, so far, always been at stake here, by his own admission, was the possibility of synthetic a priori judgment, not an “intuition” stricto sensu, and it is absolutely essential that we maintain this distinction. This distinction can be further refined—if the synthetic a priori is not an intuition stricto sensu, that is not to say that it is not an intuition in any sense. I do think synthetic a priori judgment can be considered a sort of intuition—an analytic intuition (not an analytic judgment). That is, synthetic a priori judgment is an “extuition”, and, in terms of generic ambiguity, it is fair to call extuition a type of intuition. Intuition, in the usual sense, is an inwardly directed “seeing”, an im-mediate cognition (or intellection)—that is, in reference to intuition, there is no transcendental or discursive “realm” mediating the simple unity of subject and object. Whereas, the synthetic a priori judgment is mediated by the sense impressions of the transcendental subject—that is, the a priori element here is mediated by the a posteriori one, and indeed vice versa. Moreover, we must also take into account that it is always mediated for someone—that is, as already mentioned, these are sense impressions for the transcendental subject. In fact, from the standpoint intellection, whether passive or active, it is the transcendental subject who does the mediating between the two intellects—that is, the transcendental subject stands juxtaposed between them, as it were. From the standpoint of the lawful transcendental subject (that is, the subject insofar as it obeys the Kantian injunction to turn only toward “possible experience”), passive intellection mediates active intellection (sense impressions mediate our a priori concepts), and active intellection mediates passive intellection (our a priori concepts mediate the form of our sensibility) [1]. Or, rather, that which stands for passive intellection mediates that which stands for active intellection, and vice versa. The transcendental subject is, in a sense, a realm of pure mediation, the “realm of Hermes”, wherein sensibility and a priori form are mediated by the subject, the subject's sensibility is mediated by a priori form, and a priori form is mediated for the subject by sensibility. That said, it is not passive intellection “as such” (or being-in-the-world) which concerns the transcendental subject, but the transcendental analogue of this being-in-the-world in the form of sense impressions. It is is that which stands for passive intellection, from a transcendental standpoint. Nor is the transcendental subject concerned with active intellection “as such”, but with its transcendental analogue in the form of a priori concepts (or forms of sensibility)—the abstraction of active intellection. It is that which stands for active intellection, from a transcendental standpoint. The transcendental subject is always and everywhere only concerned with itself, with its own alienated self-expressions. In every face it sees only its own reflection, in every voice it hears its own echo, and yet it wanders bewildered, as if in a foreign land, finding every day something new, strange, and uncanny. Narcissism is, in fact, impossible. Which is to say, it is a delusion. The narcissist merely believes that he encounters himself everywhere, but he does not ever know it. The transcendental subject cannot ever know, in a genuine sense, because the transcendental subject is ignorance unbound, illusion triumphant (and this, by no means, makes it any less scientific). The delusion of narcissism, at the same time, is the most characteristic kind that the transcendental subject can succumb to, and the closest that it arrives to its own truth. This proximity is not that of a degree of truthfulness, however, but of a nearness to its borders—which is to say, this nearness to truth is not truth at all, but falseness outright (we are either within the borders of truth or outside of it). Narcissism is a resemblance of transcendent truth, “the ape of God”, and an obstacle to transcendental science. That is why “mysticism” has ever been characterized as “navel-gazing”, and why the scientific thinker (= the lawful transcendental subject = the Kantian subject) must always be the very opposite of a narcissist, ever turning his impassioned curiosity outwards, never concerned with himself. That is, he must never know that, as transcendental subject, all he ever encounters is himself. Indeed, he never does know it, but as a narcissist he might even believe it. The transcendental subject never knows, but always ranges into the unknown, re-producing its own inscrutable image in every crevice of the crumbling monolith of the real. Narcissism, then, masquerades as truth because it fears the unknown, hiding from its own inscrutable nature by pretending that it knows itself, by fashioning itself into something merely knowable (and even then, not at all in a genuinely intellective sense of “knowledge”). Is our age, then, not a narcissistic one? We know everything, and repeat everything that we know again and again. We are not a genuinely scientific age any longer. If today we “trust the science” that is because science is no longer cunning. We have debased it by rendering it worthy of trust, divesting it of all subterfuge and treachery. If today's science takes us to the abyss, it nevertheless does not betray us—we have consented to this. A science capable of real treachery might yet save us. Our science, however, is certain in what it knows and we must be certain in it, in the discursive formulas and slogans that it repeats endlessly. “When we leap into the unknown, we prove we are free”—on this point, too, the culture of sequels and franchises is in basic disagreement. If our culture is a narcissistic one it is because it fears the possibility of a scientific culture, a culture of megaliths, a culture of Titans. There is no “return” to the parochial. It is either Prometheus or Narcissus. These are the princes of the age, a prince of the all-penetrating air and a prince of reflections on the surface of the water. To exit the “goon cave” of contemporary culture, we must elevate Kant to godhood, and refashion him in the image of a Promethean hero.

1: What of the unlawful subject, who turns toward abstract contemplations, divorced from Kantian rigor? Here a posteriori concepts are given a freer rein. Discursivity acts unrestrained. There is, therefore, a marked tendency toward sophistry, but at the same time a wider scope for creativity and revolutionary thinking.

*

“...things as they are in themselves...cannot migrate into my faculty of representation”

(24)

As indicated here, it is primarily a question of the being of things (“things as they are”), and, moreover, it is their im-mediate being which is of concern here. Representation, therefore, is taken to be something which mediates being, and this therefore intimates, at least implicitly, that representation is a sort of “non-being”, or partakes of the character of non-being, though, in this case, abstract non-being as opposed to metaphysical non-being (“All-Possibility” in Guenon's terms). Putting representation aside, for the moment, and returning to the question of being, it seems that the being of things can be encountered, broadly, in two ways—passive intellection and active intellection (with the unity of these two intellects in “primordial intellection” constituting a sort of third way). It is in this way that things are encountered as they are, in their being. Re-presentation comes in whenever we wish (though, strictly speaking, it is not really a matter of anything as haphazard as “wishing”) to enumerate the properties of things, the possibly [1] enumerable properties of things, their possible conceptualizations. Things already present themselves once, in their immediate presence to intellect. Re-presentation presents them again in whatever ways they prove susceptible of being present again. These possibilities are contained in advance within the original intellective act as “nothings”, as puzzling or mysterious aspects of the original “cognition” (a term which is not exactly adequate to intellection, but serviceable enough) which the mimetic faculty of representation repeats and re-images as “somethings”. It is our wondering and inquiring about the puzzling aspects of that which seems obvious (intellection) that is productive of our re-presentation of things, our translation of synthetic whole (intellection) into synthetic judgment (a priori concept; form of sensibility). Here we must distinguish between the representations which occur more-or-less “automatically”, and those which are the product of the creative activity of an artist or philosopher. The former appear “natural”, and Kant classifies the knowledge of them as constituting a “philosophia definitiva”, though in reality they are the products of man's social and cultural contexts—but is there really any contradiction here? For man, artifice is nature, and the edifice of modern science is the abstract universality of the Earth, the triumph and reign of Prometheus. The rigorously constituted and lawful subject, as elaborated by Kant, the scientific subject, is as inevitable as industrial society, the eminently scientific society. Communism is this same science as applied to the organization of the social and political sphere, a science of the Earth as a polity. This science cuts like an ice-cold razor against the boundaries of Dasein, but like a razor in its precision it can just as well cut around when employed skillfully. It is always, however, cold to the touch, without respect for cultural parochiality. Its audacity inspires fear. It is not the monster hiding in the closet but the monster we must all become, the monster looking back at us in the mirror—a Titan, our Titanic future. It is we who lurk in the closet of narcissistic distraction, lest we encounter the monster ranging freely in the bedroom.

In any case, and returning to the distinction between judgment and intellection, it is our immediate intuition of qualitative mathematics (as in that of the Pythagoreans), for instance, even if only on a passive level (e.g. our worldly, “gut” sense of unity and multiplicity), that makes re-presentative mathematics (e.g. geometry, in the quantitative and applied sense) possible. Qualitative mathematics is the ground of possibility for the various quantitative mathematics. It is intuitive mathematics which makes conceptual mathematics possible [2]. Returning to the question non-being—it is the abstract non-being of representation (and, consequently, of the representor, i.e. the transcendental subject, which is, itself, at the same time, a re-presentation of intellect) that allows it to “take” being-as-it-shows-itself (through intellection) and force it to show itself again (i.e. re-present what it did not, originally, show—its non-being). That which being did not show is not, lacks being—hence, it is precisely through interposing nothing into being that the transcendental subject modifies the contours of being and, in a sense, re-imagines being, that is, re-situates the intellective within the domain of transcendental imagination [3]. Guenon is rightfully adamant that metaphysical non-Being is not “nothing”, and yet we might insist that indeed non-Being manifests itself impossibly as nothing, through the manifold typology of nothing. That “nothing” is an impossibility, is a point on which Guenon would agree!

1: Again, potency would be more to the point. To invoke “possibility” is not, however, incorrect. The potential and the actual are equally possible. “Potentiality” would, nevertheless, be more precise in this context. These conceptualizations are potencies inhering in the intelligible situation of transcendentality in the midst of transcendence.

2: That is, from a transcendent standpoint. From a transcendental standpoint, we could also consider the intelligibility that “takes thought as a preliminary” (see my notes on Aristotle’s De Anima). The possibility of “driving both ways” here (or, better yet, perhaps, the assertive impossibility) points out the generically ambiguous character of mathematics, the meaningful emptiness of its symbols and signs.

3: That is, imagination within the horizon of anticipatory thought, Promethean thought (pro-mathein). To be distinguished from the imaginal (the “mundus imaginalis”), the interweaving of imagination and genuine knowledge, gnosense.

*

“...intuition contains nothing but the form of sensibility, which in me as subject precedes all actual impressions through which I am affected by objects”

(24)

As already suggested before, it does not suffice to simply say “form of sensibility”—we must specify for whom this form has pertinence in this or that case (and therefore, also, in what sense it is a “form”, a term which is obviously equivocal or, better yet, generically ambiguous). Kant here makes it clear that he is delineating the form which sensibility possesses for the transcendental subject [1] (as opposed to that form which it possesses for Dasein, for instance), for whom sensibility has the tripartite structure of a subject-object relation—a three part formula: subject, object, and the relation between them. It is this particular form of sensibility (particular to the transcendental subject [2]) that Kant's project attempts to delineate, a task which he takes up with unparalleled rigor. This relation primarily has the form of synthetic a priori judgment, which “unravels” itself through analytic a priori judgements (a process whose endpoint is determined by the analytic a posteriori judgment [3]), and acts as the “space” for synthetic a posteriori judgments. This is a form of sensibility which is predominately abstract and conceptual, though “intellective concreteness” is not entirely excluded—it seeps in like a specter haunting the edifice of the transcendental condition, that which defies the abstract structures (moirai) synthetic a priori judgment establishes in advance, and frequently has the appearance of a paradox (for the transcendental subject). Intellection, seemingly, is a nothing for transcendental subjectivity, that which eludes the transcendental horizon, that which, like a ghost, walks through its doorways and walls, transgresses its abstract laws. Naturally, intellect, from its own standpoint (whether passive, or active, or both), has its own forms of sensibility. We refer to the sensibility of intellect as gnosense (an adaptation of the Arabic “dhawq”).

1: Naturally—for whom else would would Kant delineate? I only point it out lest we take this obviousness for granted. It should give us pause to reflect, especially upon alternatives.

2: Though, transposable beyond its horizon through the “medium” of generic ambiguity.

3: In this regard, we can and should distinguish between a posteriori analysis and analytic a posteriori judgment. The former conditions “how far” we push our synthetic a priori forms of sensibility. In the case of Kant, we push them out to the border of things-in-themselves, the last of the forms of sensibility, as it were, but only a virtual form of sensibility, the horizon that conditions the scientific appraisal of objects and appearances for the lawful transcendental subject. The latter determines how far we pursue the division of our world and concepts, within the transcendental horizon. Thus, the difference—a posteriori analysis traces the contours of the transcendental horizon and analytic a posteriori judgment determines the “atoms” internal to this horizon, the smallest possible constituents (as small as we need them to be, as small as we like) of which the world sheltered within this horizon is constituted.

*

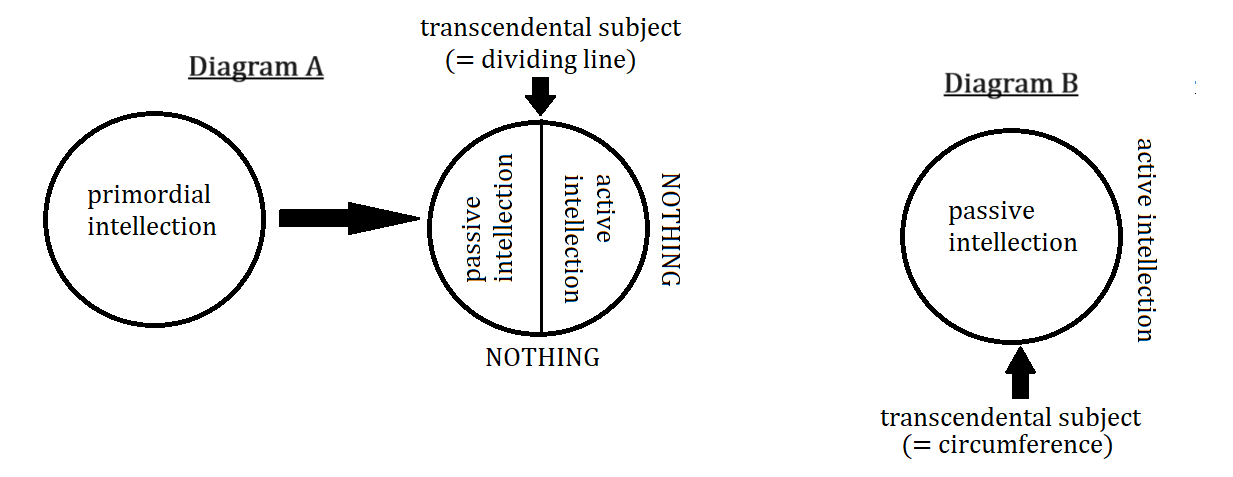

Regarding the transcendental deduction: Is it possible to make a transcendental deduction “justifying” (interesting word, in this context) the very “act” of transcendental deduction (or the synthetic a priori judgment)—that is, a transcendental deduction of the transcendental deduction? It seems that, since the synthetic a priori judgment is the very architecture of transcendental subjectivity (indeed, the very architecture of justification—though, and this will have to be elaborated elsewhere, we can distinguish between intellective justice and discursive justice), the moment we wish to step beyond the transcendental subject toward the conditions of its own possibility, we must cease to speak in transcendental terms altogether, and begin to speak in transcendent ones. That is, the condition of the synthetic a priori judgment's possibility [1] is not another synthetic a priori judgment, but an intellective synthesis. This synthesis is not reducible to a before (a priori) or an after (a posteriori), but is an always that finds itself perpetually before and after, at one and the same time, and, in a certain sense, in one and the same way (that “way” being the identity of passive and active intellect in primordial intellection). The intellective synthesis is not so much sequential (whether in a temporal or conceptual sense) as it is perennial. This is a “synthesis a perenni”, the synthesis from always, the synthesis from in front (passive intellection) and behind (active intellection)—that is, in front or behind the lawful transcendental subject: [2]

“Perennis” is literally “per annum”, or “throughout the year”, pervading the entirety of a closed cycle—that is, established according to the circle of timeless time (cf. Eliade in Sacred and Profane). One could also think of this “annum” as the circle of passive and active intellection (especially in light of their “relative timelessness”) which is “created” through the division of primordial intellection by the interposition of the transcendental subject. The synthesis a perenni [3] is that which flanks the transcendental subject from before and behind, which serves as the ground of its possibility, of its particular possibilities. Its “possibility as such” has no ground since it is nothing and indeed impossible (moreover, this nothing, as metaphysical non-being, is the ground of intellection itself)—rather, it is the particularity of its nothingness which demands a ground. The transcendental subject itself is the intrusion of a nothing into the field of primordial intellection. Hence, traditionally, metaphysical ascesis aims to return to the primordial simplicity which precedes the intervention of transcendental subjectivity, and attempts to effect this return by dissolving transcendental subjectivity—unfortunately, it never yet occurred to these men of tradition to take transcendental subjectivity as the stepping stone to a further stage of ontological development, a Promethean ontology. In any case, that nothing (metaphysical non-being), which “precedes” the circle of intellection, is both the condition of intellect's possibility, its being what it is, and the condition of its impossibility, its being what it is not (through a transgressive mimesis). In other words, intellect is the condition of the transcendental subject's particular possibilities (and hence of synthetic a priori judgment's possibility), and the transcendental subject (as a nothing, and an analogue of the no-thing, an analogue of metaphysical non-being) is the condition of the impossibility of the two intellects [4]. Below we have two ways of representing this division of primordial intellect. In the first, primordial intellect is represented as a circle cut in twain by the subject, and producing the regions of passive and active intellection as its hemispheres (or, rather, here represented as semicircles, but spherical symbolism will have relevance for us later on). In the second, primordial intellection is implied as a limitless space in which a circle appears (hence, it is not pointed out in the diagram directly), dividing that space into an inner (passive) and outer (active) region. That circle, a virtuality and a nothing, is the transcendental condition. Whether active intellection constitutes the interior of the circle, in this figuration, or its exterior, is immaterial.

For more on the kind of thinking implied in the second diagram, consult the work of the very unusual Joseph P. Farrell, specifically his formulation of the “topological metaphor”, for which he draws on the work of mathematician George Spencer-Brown.

1: Or, rather, speaking strictly, the condition of its impossibility.

2: Recall, as established above, that the transcendental subject only turns virtually toward passive intellect, turns toward what “stands in” for passive intellect, namely, the world of sensibility. It does this through its virtual appropriation of active intellect, in the form of a priori synthetic judgments.

3: There is no substantial difference between “intellective synthesis” and “synthesis a perenni”. The latter term only serves to draw attention to the symbolism of the “circle of the year”, the relation between transcendentality and the halves of this circle, thus invoking both intellects simultaneously, as well as situating intellect in the terminological context of Kant's a priori and a posteriori distinctions.

4: “Impossible”, because primordial intellection cannot be sundered.

*

“...the notion that space and time are actual qualities inherent in things in themselves”

(27)

“Things in themselves”, as Kant has already established elsewhere (p.24), means “things as they are in themselves” [1], in their being or, in any case, the being of these “things-in-themselves” is always somehow alluded to through their invocation. Thus, the space and time of judgment (synthetic a priori) is not the space and time of being (though, judgment also is, in certain conventional respects), but of the mediating transcendental subject. Judgment does not pertain to being, but to the peculiar non-being of transcendental subjectivity, a virtual non-being that interposes itself between the two modes of intellection. Space and time for the transcendental subject are the space and time of res extensa, of “neutral” judgmental discernment, of quantitative measures and ratios.

1: Was it a mere slip of the tongue? If so, it was an auspicious one. Fate slipped into Kant's speech. We will, therefore, take him at his word, as we would an oracle of the solar deity.

*

“If two things are equal in all respects as much as can be ascertained by all means possible, quantitatively and qualitatively”

(27)

Equality, in a transcendental sense, refers to interchangeablity, standardization, discursive translatability. To distribute the notion of equality equally (pun intended) to quantity and quality (as opposed to applying the term analagously, which implies, rather, a kind of “typological equality”) is to produce a conflation which is entirely fallacious. Equality, insofar as it refers to quality, can refer to co-participation in the self-same qualities, but not to discursive translatability or interchangeable and standardized parts. These are two (among others) broad and distinct types of equality (qualitative and quantitative). Quantitative equality and qualitative equality are “typologically equal” (that is, they are equally types of equality), but their equality does not subsist on the same “plane”.

*

“...this substitution would not occasion the least recognizable difference”

(27)

Here we must ask—“but who is the one doing the re-cognizing? To whom belongs this re-cognition, this second 'addititive' cognition?”. There are two cognitions here, not only in number but in kind. There is one immediate cognition belonging to intellect, and a second belonging to the transcendental subject. The second cognition is a judgmental cognition, a cognition which renders things subject to exchangeable “quantities”—no wonder, then, that it cognizes no difference! I think it is fair to assume that Kant would have proven most unsuitable in the task of constructing a yantra. In any case, and to be clear, even the transcendental subject can cognize differences here, but according to its synthetic a posteriori judgment rather than its a priori categories.

*

“...two spherical triangles...”

(27)

At first, I was puzzled by Kant's choice of spherical triangles in order to demonstrate his point. Why specifically spherical triangles? Why not two triangles with opposite orientations, one upward and one downward? The reason is precisely because he (or the transcendental subject on whose behalf he is composing these thoughts) does not recognize (re-cognize) quality “as such”, e.g. upwardness and downwardness. Upwardness and downwardness belong to the immediate cognition of intellect, not to the re-cognition of the transcendental subject. The latter recognizes only a relative up and down, that is, relative to a point of reference in extended space, a neutral space without up and down as inhering qualities but as heuristic distinctions (it is conventional and convenient to designate this direction as “up” and that one as “down”). It does not recognize the genuine intelligibility of upwardness and downwardness. The transcendental subject vacates intelligibility.

*

“...images in a mirror...[posses] no internal differences which our understanding could determine by thinking alone”

(27)

As Kant puts it, such mirror images could never serve as “substitutes” for one another—but what sort of substitution is possible here? Kant here “laments”, as it were, the element of irreducible quality that will not succumb to abstraction and judgmental standardization. It is their distinct orientations (and orientation is a basic form of symbolic quality) that refuses such a reduction. Indeed, the “internal differences” which Kant seeks are precisely those internal to (we must always ask “internal to what?”) our thinking, the internal abstract structure which is attributable to such mirror images. What, if anything, does symbolic orientation allow itself to be reduced to?—to conventional heuristic, to an up and down for-my-purposes-at-this-moment. This is the transcendental reduction of orientation, a transposition of symbolic orientation onto orientation as discursive heuristic. Transcendental reduction is the “translation” of intelligible symbol into the language of discursive concepts. Such a translation lies behind the production of all the a priori categories of judgment from out of intellective synthesis. This is not necessarily to say that there is some kind of operation called a “transcendental reduction” which one applies in order to produce the synthetic a priori forms of sensibility. These a priori forms are themselves transcendental reductions of the intellective.

*

“What is the solution? These objects are not representations of things as they are in themselves, and as some pure understanding would cognize them, but sensuous intuitions...whose possibility rests upon the relation of certain things unknown”

(27-28)

Kant has revealed here more than he suspects. Such poorly named “sensuous intuitions” (in reality, such a term could only adequately refer to gnosense, and in a way also to passive intellection, though this is by no means how Kant uses it), or more precisely synthetic a priori judgments, rest and depend upon the unknown—not the unknowable, but that which has been made unknown through an unknowing. What is it which has been made unknown? Precisely that which is most eminently knowable, that which a “pure understanding” might “cognize”, as it were. Such a tremendous deed as this, rendering that which is most eminently knowable as something entirely unknown, could only be accomplished by the transcendental subject (and in this we have a presaging of its heroic [1] and Promethean mode). Such “objects” as Kant refers to, therefore, are precisely re-presentations of things-as-they-are-in-themselves (i.e. in their being, in their original presentation). That is, things-as-they-are are presented again but this time as they are not, in their abstractable non-being. That is, this holds insofar as the transcendental subject attempts to grapple with these “objects”. Indeed, it is for the transcendental subject that they become “objects” in the “ontic” sense. Things-as-they-are do not present themselves as objects, but they do re-present themselves as such. Man does not, in the first instance, cognize as subject, but he does re-cognize as such. In any case, insofar as the synthetic a priori judgment rests upon a divestment of being—knowing and being are inextricably linked. To divest from being is also, therefore, to unknow (and to “know”, in the eminent sense, means to establish identity through an intellection). Things cease to be what they are and become for us that which they are not; not a generic non-being, but their own peculiar non-being, that non-being which is abstractable from out of them.

1: I have made a number of allusions, several in my notes and at least once in my series on “communist metaphysics” (in the opening paragraph of the first part, for instance), to a “heroic transcendental subject”, but have refrained from explaining this term's significance. The reason I designate it “heroic” is not a purely romantic one, as it were, but in reference to a symbolic motif, going back to preclassical antiquity, which in archaeological literature is sometimes referred to as the “dompteur”. This imagery inspired a certain conception of the transcendental subject in me, wherein this subject, like a Gilgamesh or some unknown Minoan goddess, grasps the two poles of intellect in its god-like arms, the passive and the active, and directs their force according to its own aims. All statements related to this subject's “heroism” have, in my own mind, referred precisely to this imagery and its implications in my conception of the transcendental subject.

From McEvilley's “Shape of Ancient Thought”