Notes on Heidegger's Being and Time, Part VI

Archeimicity and authenticity, integral sociality, the world-fracture, and backwardly progressive liberation

Harihara, 18th century

*

—Summary of insights, aka tl;dr:

Heidegger’s “They” (das Man) has a certain analogy with Plato’s form of the Good, as a stupidity that exceeds intelligibility. Transcendental subjectivity is a specification of this stupidity.

The obscuration of intellect begins with the theoretical exclusion of non-Being. This historical enfeeblement of intellect lends strength to the rise of (modern) science.

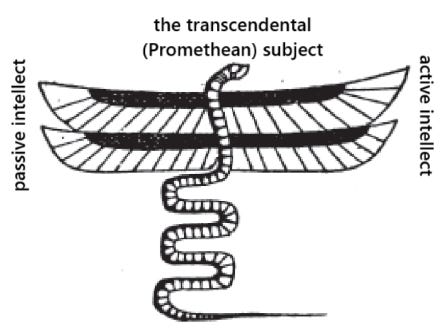

When fully radicalized, the liberatory political project involves a return to intellective origins, claiming them for itself. This stage of liberatory politics is represented by the symbol of the “winged serpent”.

Behind Heidegger’s anti-semitism and his misgivings about technology lies a very real fear of proletarian dictatorship, the institution which actualizes that which is most problematic for him about both of the former.

Any symbolism which is applicable to active intellect is also valid for passive intellect, and vice versa.

What Heidegger calls “being-in”, for Dasein, is none other than “noeisis” or intellection.

Perennialism is both the truth of Tradition and that which undermines it. This dialectical contradiction has its symbol in the myth of Atlantis.

Heidegger’s account of everydayness does not possess the normative scope he accords it. It is merely one variety of everydayness, occurring under “special” historical conditions.

The “authenticity” of Dasein is fundamentally self-undermining, and “inauthentic” Dasein is alaways basically more “grounded”.

Over and against mere “authenticity” we must posit “archeimicity”. What the former is for caprigenetic Dasein, the latter is for Dasein “as such”.

Preoccupation with “authenticity” is a flight from the more pressing task of reconstituting the intelligible unity of the social space. For Heidegger, this flight is quite inevitable since this task, in the present historical moment, necessarily belongs to communism.

Anxiety is a disclosure of the fracture character of caprigenetic Dasein.

*

“The average understanding of the reader will never be able to decide what has been drawn from primordial sources with a struggle and how much is just gossip...The average understanding will not even want such a distinction, will not have need of it, since, after all, it understands everything...[it] not only divests us of the task of genuine understanding, but develops an indifferent intelligibility for which nothing is closed off any longer”

(163)

This “indifferent intelligibility” is precisely what Socrates, “the gadfly” of Athens, sought to expose—but what exactly is this superficial sort of understanding? “Superficiality” is equivocal. The “superficiality” of the transcendental subject's conceptual thought cannot be the one in question here. It is superficial, yes, but it certainly does not, from the outset, pretend to understand everything. It is constantly assailed by doubts, continually refines distinctions, and it certainly cannot be justly equated with mere “gossip”. Indeed, the philosophical tendency which begins with Socrates is simultaneously characterized by such “transcendentality” as it is by the transcendent (the Presocratics were, comparatively, weighted more heavily on the side of transcendence alone). Descartes did not originate a transcendental turn in philosophy, “as such”, but an exclusively (more or less) transcendental turn—that is, his contribution was primarily negative (though no less profound in its impact, for that reason). What, then, is this “indifferent intelligibility”? Heidegger seems to identify it with “the They” (das Man). Plato identifies it with “shadows”, and it seems worth noting that, in his allegory, the “shadows” are socially mediated through language. The prisoners compete in naming the shadows, and their identification of these entities seems to hinge on confirmation by their peers (who would dare name them in isolation but a madman? Everything must be corroborated by “the They”). Their relation with the “shadows” is socially mediated, and their relation with each other is mediated by shadows (they encounter each other through their “shadow games”; cf. “language games”). Heidegger's expressions “average intelligibility” and “indifferent intelligibility” clue us in that we are dealing with a mode of being (i.e. because it is a genuine kind of intelligibility which is in question), and not so much with the ontologically privative character of transcendental subjectivity (is it any wonder that Kant excluded “being” from predication? [1]). Both the “transcendental scholar” and the metaphysical sage will tend to feel contempt for the lackadaisical self-satisfaction of this “indifferent intelligibility”. And yet, one is nevertheless tempted to associate this “indifferent intelligibility” with transcendental subjectivity—not, however, to locate its origin in transcendental subjectivity, but just the reverse. It is transcendental subjectivity, as a type of nothing, which has its origin in this vaster sort of nothing—in victorious and all-conquering stupidity. Transcendental subjectivity (I mean transcendental subjectivity, particularly, at the acme of its development) is a specification of stupidity, a type of stupidity, a cunning stupidity, scientific stupidity. It is fire, harnessed and controlled by Prometheus, not the all-potent source beyond the heavens (“Form of the Good”). Among “the They”, stupidity does not yet become specified. In being specified, transcendental subjectivity mediates the “higher and lower waters” (that is, active and passive intellection). “The They” also “mediates” something. It mediates the unintelligibility of the Absolute (“Absolute”, here, in the sense of “the Form of the Good”, not the Hegelian Absolute—the latter is really just the acme of specified stupidity, i.e. of transcendental subjectivity). This is one meaning of “the masses are God” (Mao: “Our God is none other than the masses of the Chinese people”), for Promethean socialism. The masses are emblems not of the mere Heavens, but of that which lies beyond the Heavens, the very Form of the Good. The masses are a mystery, the sirr al asrar. One can never understand them, because they are beyond understanding (para-dox)—as all stupidity must be beyond understanding [2]. The Form of the Good, too, is a shadow, a divine darkness obscured by the light of the sun—beyond the sun is a second cave.

One could say, then, that this “indifferent intelligibility” is an indifference to intelligibility. It circumvents intelligibility, dances around it like a mocking imp, handles it playfully and carelessly. Transcendental subjectivity, on the other hand, is specified in the way it handles intelligibility, and this specification has the character of a mimesis of intelligibility. It imitates intelligibility's outward forms, takes it seriously. If stupidity is an imp, then transcendental subjectivity is a gargoyle—it broods. Indeed, fear is a specification of joy, the concentration of vital energies, as opposed to its dissipation through joy. The Upanishads tell us “Thou art That”—one could equally say “(the) They art That”. “The They” are the divine mystery in the mode of obscenity, the witch's sabbath. The aforementioned connection with “language” seems to be that “the They” handle language with a characteristic laxity. “Discourse”, which for Heidegger is the structuring factor in the world's intelligibility, becomes the instrument through which intelligibility is mocked and circumvented. Language becomes a game, a playing with shadows. Games, then, are also the characteristic activity of the They. It is playing and joking which links us to “the They”, above all. Science is grounded in stupid witticisms. The earliest natural philosophers were laughed at.

1: Predication is, at first glance, a grammatical function. In a philosophical context (let us say, of lowercase “p” philosophy), it pertains merely to the way we can speak about things, and seemingly presumes the total adequacy of discursability to all that which is (= being). When we ascribe being to that which is, we have not said anything about it that we have not already presumed. Looking beyond mere grammar, there is a whole metaphysics implied here. This metaphysics states—“only being is the real, and nothing else”. This metaphysical commitment is the preliminary to the transcendental turn. The beyond-being (or non-being, which is effectively the same) of Plato's Form of the Good is excluded here. Possibility is narrowed to an identification with potentiality and then, after the transcendental turn, reduced to mere virtuality. The actual, in turn, is somehow neither possible nor impossible—it just is, and being is no longer a predicate of the possible, but the ever narrowing horizon of discourse. We have elbowed out the “Neoplatonists” and consigned them to the category of mere “mysticism”. Of the Proclean reality-spanning Triad, all that remains is the narrowest sliver at the edge of corporeality. The super-intelligible ecstasy of the One is no more, and if that upon which intelligibility subsists is no more, then intelligibility itself must grow feeble.

It is a curious thing that the historical enfeeblement of intellect has lent nigh unconquerable strength to human science. A phase, however, is not a permanent state of affairs, but a dialectical moment. That which acted in a certain way at a certain time is not bound to effect itself in the same way at all times. If, in the lead up to the present, the disappearance of intellect has meant the appearance of modern science, in the fullness of its vigor, it does not follow that this correlation holds good for the future. The positioning of these elements in the dialectical movement must be accounted for, and the intelligible context of history as a whole—yes, intelligibility itself takes the lead and returns like a deus ex machina. Intelligibility never really “disappears”, but fades into the background (and, as a background, intelligibility is still as fully operative as ever). It obtrudes into the foreground when we least expect it.

Whether or not the gods will be “allowed” in our communist republic is a question for utopians. Their presence or absence is a function of their position in the dialectical movement at any given historical moment. The question of atheism or theism, too, is but a movement and a series of overturnings, in the course of which their very meaning changes. One cannot hold fast to either in ideal permanence, and the theism of one era can be more of a scandal to the theism of another than any atheism. The “scientific” atheism of the 19th century was but an intellectual fad—communism is a real movement.

2: It is proletarian dictatorship which disciplines and specifies them, amplifies their scientific cunning. This process begins already with class struggle, and so on.

*

“Idle talk is a closing off since it omits going back to the foundation of what is being talked about”

(163)

It seems that the whole Cartesian tradition consists in a comparable “closing off”, and in Hegel this closing-off “doubles” when the circle of the so-called “Absolute” closes in on itself. The closing-off accomplished by the Cartesian tradition is precisely a closing-off of “foundations”, in this case of “intuition” (intellect), from which foundation the modern philosophical tradition's concepts (e.g. substance, being, etc) were originally derived. Nonetheless, this closing-off did not originally result in total inertness, but in a “line” capable of directed inquiry. Moreover, through Kant, this “line” acquired self-clarification (through the “transcendental deduction”), and through this clarification a greater precision in its concepts and thus also an amplification of its powers of directed inquiry. Through Hegel, the power of directed inquiry is, initially (see: Marx), lost. The Hegelian line of inquiry turns in on itself and forms a closed circle (or a seemingly closed circle—every hermeneutic circle only seems to be closed). That which, initially (through Descartes) was only closed to intellect is now also closed to further progress in inquiry (unless, like Kojeve, we willfully amputate philosophy into natural science and historical philosophy). With Marx, this Hegelian circularity is overcome, (though, to an extent, the idea of “full communism” constitutes a regressive residue). Marx liberates dialectic by converting it into a method, a double method—both for inquiry and for political action. The circle becomes a sort of “fractal” spiral with dual directionality—it can burrow inwards, through analysis, and expand outwards through “praxis”. The full consequences of this liberation of dialectic have not been adequately worked out. Moreover, it leads to an inevitable question: keeping to the just adopted figurative language, if a liberation of the line from the circle is possible (a liberation which is an “aufhebung” since the line now possesses the “power” of circularity in the form of spiralation [1]), then why is not a liberation of the spiraling line from the narrow limits of the plane also possible, that is, a liberation of science from Cartesian-imposed limits (i.e. the foreclosing of intelligibility)? Incidentally, this “backwardly progressive liberation” (here we go back to pre-Cartesian intellect) has the same form as the “revolutionary return to tradition” (see my short essay “Marx's Retvrn to Tradition”). Thus, the next stage in this “backwards liberation” consists in the acquisition of intellective powers by the spiral of dialectical inquiry. The spiral of dialectic is, initially, flat, that is, situated on a plane. It is a spiraling around on the surface. The next stage in the process of “backwards liberation” returns to the level of the hermenoetic sphere, and thus acquires the power of spiralation in three dimensions, which is to say that it acquires intellective flight. The spiral has become a winged serpent. Marxism (or communism) becomes none other than the process of mankind liberating its own liberator (Prometheus, the serpent of Genesis) in the process of its own liberation. Returning to the initial topic of “idle talk”, it becomes clear that it is Hegel, especially, whose philosophy consists in “idle talk”—it not only cuts itself off from intellective sources (as do Descartes, Kant et al), but also willfully aims at going nowhere because it already “knows everything”. A further question should be posed here: is there a further step in the process of “backwards liberation”, perhaps corresponding the true Absolute (in the original, metaphysical sense)? Possibly, but it belongs to a quite distant historical stage, and one can only speculate as to its practical content. Hypothetically, one might also wonder whether this process of “backwards liberation”, once it reaches its metaphysical terminus, might then inaugurate a process of “forward development” which, in turn, will lead to another process of “backwards liberation”, and so on, ad infinitum. This is all very speculative, but worth thinking about. Also worth speculating as to where the “indifferent intelligibility” explored in the previous reflection fits into this scheme (arguably, the “space” in which this “winged serpent” flies is always, initially, “indifferently intelligible”; “initially”—i.e. because, through flight, it creates intelligibility in its wake).

1: Cf. Marx's dissertation on Epicurus: “Just as the point is negated [aufgehoben] in the line...”

*

“All genuine understanding...Come about in [the They], out of it, and against it...The They prescribes that attunement”

(163-164)

This confirms the above hypothesis, i.e. that “indifferent intelligibility” (which is, functionally, the same as to say “the They”) is the space in which an intellective “subject” moves. The They is inconspicuously intelligible sociality. We should not, like Heidegger, suppose that the model of such a sociality furnished for us by our present environment is exemplary of such a sociality as such. Just as Heidegger's Dasein is, for the most part, caprigenetic, so is the They, as he accounts for it. This particular instantiation of what Heidegger calls “the They” is a highly peculiar qua “inconspicuously intelligible sociality”—but more on this later.

*

“Being is what discovers itself in pure intuitive perception, and only this seeing discovers being. Primordial and genuine truth lies in pure intuition. This thesis henceforth remains the foundation of Western philosophy. The Hegelian dialectic has its motivation in it...What is this tendency to just-perceive about?...Taking care does not disappear in rest, but circumspection becomes free, it is no longer bound to the work-world...it tends to leave things nearest at hand for a distant and strange world. Care turns into taking care of possibilities, resting and staying to see the 'world' only in its outward appearance”

(165-166)

This view which he attributes to antique philosophy, here with reference to Aristotle or Parmenides, seems, initially, to be straightforwardly accurate . That is, the initial formula, given above, as pertains to the relationship between being and intuition, seems to be perfectly correct. It is, however, the interpretation Heidegger gives this formula which is crucial. This interpretation is par the course for Heidegger—intuition is “just-perceiving”, a seeing of the world only in its “outward appearance”, and philosophical modernity is to be read backwards into antiquity. A valid point about Hegelian dialectic becomes an invalid one about ancient metaphysics. There is room, then, to say something here about the Phenomenology and the Logic. After all, as Heidegger carefully stipulates, this “just seeing” does not only refer to the faculty of sight, even if a certain preferential connection with sight persists from antiquity. This manner of just seeing could be legitimately extended to include the “just-positing” or “just-thinking-about” being and nothing of the Logic. Both are expressions of the same kind of “curiosity”, as Heidegger terms it, the products of the subject's otium (or that of caprigenetic Dasein).

A more precise delineation of the kind of “otium” that Heidegger uncovers here, and an explication of its ontological significance, would be appropriate. This otium is attended by boredom. It looks around for something to do, anything at all. It is not a genuinely contemplative rest, but the rest of the thinker (or, really, any kind of busybody). It is not a rest which abides in its own being, that is, a rest which rests. Indeed, inconspicuous being-in-the-work-world is ontologically closer to genuine rest than this otium of the busybody. This otium is an interruption of the rest which abides in being, including that “rest” which abides as inconspicuous taking care in the work-world. Hence, such an otium is directly analogous to the breakdown of the tool, in Heidegger's ontology. It is, thus, a kind of proto-transcendental condition (at minimum). In that case, this otium is that of the natural philosophers, and of their descendants in modern science. Otium, then, turns around and becomes its own opposite—otium, which is initially the recreation of aristocrats (see Nietzsche's philosophical panegyric of this “virtue”), becomes the union of science and labor, the thoughtful inquiry of busybodies, repudiated by Nietzsche's latter day disciple Heidegger.

*

“[Curiosity] seeks novelty only to leap from it again to another novelty...Curiosity has nothing to do with the contemplation that wonders at being. [It is essentially characterized as] never dwelling anywhere. Curiosity is everywhere and nowhere. This mode of being-in-the-world reveals a new kind of being of everyday Dasein, one in which it constantly uproots itself”

(166)

There is a severe moral reprimand implied in his assessment of “curiosity”. It is not only such and such a thing, which exhibits such and such characteristics—it is most definitely also bad. It is bad twice over, bad like the Jews and bad like Prometheus. Heidegger is anti-Promethean because he is an anti-Semite, and an anti-Semite because he is an anti-Promethean. These two are either identified here, or so closely entangled as to be inseparable. This is in itself most curious—is Prometheus, then, a Jew? Is Jewishness the same as Prometheaness? In fact, the “Jew = Prometheus = bad” equation can be reasonably extended as “Jew = Prometheus = Communism = bad”. Communism is the real movement of these forces, the uprooting power of modernity and the trajectory of scientific inquiry that uncovers novelty after novelty. Communism is “rootless”, internationalist, like the Jews, and inquisitive to a a fault, like Prometheus. Proletarian dictatorship, in turn, is the dread institution that asserts and realizes these forces in history, as a matter of deliberate policy, through and for the class that embodies these forces in the social field.

Heidegger's implied moral reprimand, obviously connected with a fear of real historical forces, is also premised in a refusal to wonder. Indeed, he does not err in pointing out that curiosity of this kind does not consist in a contemplation that wonders. Nevertheless, curiosity can be quite a disciplined thing, even when, at bottom, what it seeks is novelty. This is not prima facie something trivial. It can be dangerous, world-shattering. Heidegger seems not to be particularly astonished here at this world-shattering (and world-constructing) power [1], this force of liberatory impossibility. Indeed, it, too, is worthy of wonder! This power which uproots and is somehow everywhere and nowhere is, as such, awe inspiring—especially to the degree that it is constituted in such a way to exhibit these tendencies efficaciously. Where does it do this? It is through the aforementioned “dread institution” that these tendencies are exhibited most efficaciously. Proletarian dictatorship is something to wonder at.

1: This assessment obviously has to be modified, somewhat, in the case of Heidegger's later work. See especially “The Question Concerning Technology”.

*

“The falling prey of Dasein must not be interpreted as a 'fall' from a purer and higher 'primordial condition'”

(169)

Another instance of Heidegger taking Dasein's “everydayness” as ontologically normative, whereas it is really only ontically normative of certain historical and social contexts. That is, the state of “everydayness”, as Heidegger understands it, is accorded the privilege of serving as the benchmark or baseline of Dasein's way of being-in-the-world—this special privilege has not been justified. Indeed, as soon as one grasps what the faculty of “passive intellect” is, it becomes clear that such everydayness does not represent its functioning par excellence, that is, it does not represent its optimal functioning, its most characteristic functioning, its functioning as itself to the highest degree possible. How, then, can everydayness be taken, ontologically, to be “what is nearest to Dasein”? The term “higher”, in the above passage, can be misleading. Representing states of being in terms of height is more characteristic of active intellect. Passive intellect is better characterized by degrees of absorption or intensity of ecstatic being-in-the-world. In the case of passive intellect, a retreat from a primordial condition might more aptly express it, or a distraction, a forgetting (cf. the “forgetting of being”), a dulling. Regardless, Dasein's everydayness and absorption in the They can validly be described as a “fall” [1] from a purer condition, provided we do not understand this “fall” in an ontic sense. That which was not intended ontically, to begin with, cannot be faulted for a merely ontic imprecision. The symbolism of a “fall” is meaningful, ontologically, for active intellect, and the symmetry of the intellects ensures that what is meaningful for one intellect is also meaningful for the other, even if not eminently. The symbolism of the intellects is a universal currency of interpretation.

1: A fall from what? A fall from what we might call an “integral sociality”, to be distinguished from the sociality of caprigenetic Dasein in “the They”.

*

“Being-in is quite different from...a concurrent objective presence of a subject and an object” (170)

Clearly expressing the intellective character of Dasein. This, and not “staring”, not objective presence, is noesis [1]. That is, noesis is, from the standpoint of passive intellect, none other than integral and intelligible being-in. If, then, passive intellect is an “intelligible-being(-in)”, then active intellect can be characterized as an “existential knowing”, a phenomenology of contemplation, a flowing gnosensiential tapestry of identities. More specifically, we might say that it is an “existential knowing-as”, with “as” indicating the function of identity of knower and known (the knower knows as the known), the existential flow of adequational contemplation, a seamless succession of absorptions in the varied “objects” of knowledge.

1: Nous and intellect are, of course, equivalent. I use “noesis” here because Heidegger makes explicit reference to this term in this text.

*

“The self-certainty and decisiveness of the They increasingly propagate the sense that there is no need of [authenticity]...Entangled being-in-the-world, tempting itself, is at the same time tranquilizing”

(171)

Rather ironically, one of the means at our disposal for bursting through this tranquility of the They is the skilled and audacious deployment of our “Reason”, of those “inauthentic” [1] faculties that bring us to lucid (uncannily lucid) and objective presence, that cut through being and bring us to the possibility of restructuring that very world which one can relate to in the mode of being-in. The intelligible topography of worldly being can be terraformed. This requires as much “aesthetic inspiration” as it does audacious and naked reasoning. Dasein is in the world—but who has made this world for him? We do not live any “naturally” given world, but one that has been made and remade again, in the furnace of history. Prometheus is our world-maker. At the same time, however, it should be kept in view that such a terraforming activity always proceeds from out of some ground or another, that is, ontologically speaking, that activity which restructures the world for our being-in is itself already grounded in some manner of being-in. Promethean Reason determines its own grounds, but only after the fact. First, it already has a ground, and then it determines it. A truly deliberative and fundamental world-making project demands that we establish contact with these ontological origins—this is precisely the meaning of the “second ontopolitanism”. Technology or, rather, technoscience (i.e. the intersection of social being, theoretical reasoning, and technological use), itself becomes the “skillful means” (upaya, or tactillection) of the communist bodhisattva. As with the original Buddhist context of this concept, the “skill” in question is that exercised by the “enlightened” being instructing the unawakened. It is the skill and the cunning which he employs in devising methods whose aim is to establish contact with the wakeful being of those who presently sleep in samsara, not the skill they employ in following his instructions. The modern, communist Prometheus, too, must devise means which, taking advantage of the prevailing social and technological situation (chiefly, socialized production and advanced technological development), does not lose contact with those ontological origins that are, in reality, the sole source of all power and volition.

1: Some clarification on “authenticity” is needed here. One must not forget that Heidegger's “authenticity” pertains to the caprigenus Dasein, and hence is certainly related with Reason. Indeed, one could say that Dasein is implicitly culpable for inauthenticity, in and through its authenticty. This is connected with Heidegger's reflections on “guilt”, defined by him in relation to Dasein's unrealized possibilities, later on in this book. “Authentic”, I-saying Dasein is already a caprigenetic Frankenstein, and there is inauthenticity in its marrow, by virtue of its authenticity (and vice versa, authenticity is implicit to inauthentic Dasein). It is because “authentic” Dasein says “I am this finite and fateful being, rooted in the destiny of my volk” (let us not efface the racialist implications of Heidegger's notions) that it recalls every other possibility for I-saying that it has pushed aside as unfateful and inauthentic to its own destiny. Dasein is intrinsically guilty of being able to be rootless, culpable of being able to choose something other than its fate, and it is eminently reason that allows Dasein to extract itself from the integral embrace of its destiny. In this connection it is also crucial that this is a destiny and a fate that is appropriated by its I-saying, that is, an automorphic fate and an automorphic destiny, a fate and destiny belonging to the caprigenetic Dasein, and not to “simple” Dasein qua Dasein. Caprigenetic Dasein, then, is neither the end nor the beginning of this story, and neither authenticity nor inauthenticity have anything fundamental about them, ontologically speaking.

If, then, we wish to retain I-saying as a theoretical reference point, imbuing it, instead, with genuine intelligibility, and anchoring it in the aforementioned “simple” Dasein (that is, if we wish to retain I-saying tactillectively), we will need to furnish ourselves with new concepts. A term for designating “atman-centricity”, as it were, will be needed so as to distinguish it from the ahamkara-centric character of “authenticity”—tentatively, archeimicity and eimimorphosis—“arche” as indicating the principial character of the “phenomenon” in question, and “eimi” as in the “ego eimi” of the Gospel of John (“before Abraham was, I am”). Thus, archeimicity is the “prinicipial I-am-ness”, and eimimorphosis indicates the tendency of subsumption into the intelligible embrace of this principial “I am” (like Plato's Form of the Good, it bestows intelligibility, but lies beyond it). Archeimicity is principial unity and wholeness, established tactillectively with reference to our I-saying activity. The same notion, taken apart from this reference point of I-saying, is essentially what the Neoplatonists call the “henads”. In the case of the henads, and of philosophizing in the Western-Platonic mold generally, the reference point is intellective contemplation. If the central aporia of the Indian philosophical tradition is the mystery of I-saying, then that of the Western-Platonic tradition is the mystery of the possibility of knowledge, and the henads are an exceptionally refined distillation of that problem.

*

“...understanding the most foreign cultures and 'synthesizing' them with one's own...Versatile curiosity and restless knowing-it-all masquerade as a universal understanding”

(171)

A basic antipathy here between Heidegger and Guenon—passive intellect is provincial intellect or it is, at least, within a certain “provinciality” that passive intellect finds its most comfortable expression. While, strictly speaking, both active and passive intellect, as intellect, are characterized by universality, one could say that active intellect is universal par excellence, and one might, correspondingly, associate passive intellect with a sort of “ecstatic particularity” (cf. thrownness, facticity etc). This universality, at least, is a feature of intellect in our historical era (harking back, in our collective imagination, to the legendary period of “Atlantis”, which mythically represents a “scientific universality” of intellect par excellence), that is, it may be a specific kind of universality which is in question here, a historically specific manner of expressing and understanding “universality”, one that tends toward and supports something like “scientificity”. In any case, one curious feature of perennialism, a la Guenon (albeit, going back as far as Platonism), is that it is not only universal in its most basic constitution but, just as significantly, cosmopolitan in its mode of expression, and “cosmopolitan” is, socially, the equivalent of generality rather than universality. In a time like our own, where “universality” and “generality” are confused, it is tempting to conflate them and hence to misunderstand the nature of the cosmopolitan phenomenon as well as the significance of “universality” itself. Universality is a feature of intellect's operation, not a cross-cultural or historical phenomenon. Universality can (and frequently is) immanent to a tradition without spilling over to any cosmopolitanism, without expressing itself in any form that lends itself to cosmopolitanism. Cosmopolitanism is a special “addition”, mythically prefigured in Atlantis [1], which requires an advanced development of discursive Logos (though without losing sight of its symbolic dimensions). I mean, of course, “cosmopolitan tradition”, which is to say, expressions of metaphysical universality which lend themselves to cosmopolitan cultural and social forms, that is, to expression in terms of general concepts or philosophical jargon (something which seems to be connected with the rise of coinage at about the time designated as “the axial age”), not cosmopolitanism “as such” (modern cosmopolitanism, for instance, is grounded almost exclusively on the discursive and ratiocinative side). It requires such a “cosmopolitization” of tradition (which is to say, perennialism) in order to make fruitful cross-traditional contacts possible, at least on an extensive and highly communicable scale. It requires a further rootedness in the ontological or metaphysical (concerning the precise basis for the distinction between “ontology” and “metaphysics” see Guenon—in brief, whether or being or non-being is taken as primary, respectively) dimension of Tradition to prevent superficial syncretism. In that sense, perennialism is always risky. It is characteristically “Greek” (even if only in the retrospectively stereotyped sense given to us in the Renaissance) in that it requires a sense of balance and moderation, and is at the same time driven by a kind of colonizing wanderlust (though, not in the sense of the “colonial era”), or even by “curiosity” in Heidegger's sense. Perennialism, as a historical tendency, conceals a Promethean core. The “Atlantean thesis” is meant to explain why these diverse traditions already are susceptible of being identified by the category “cosmopolitan”—in a sense, they are already susceptible of being cosmopolitanized in advance. This thesis posits an “identical origin”, in some “primordial tradition”, which, subsequent to the destruction of Atlantis, was dispersed throughout the earth (considerations related to a “Hyperborean tradition” also enter into this rather nebulous “occult history”, which has a certain symbolic interest whatever the degree of its literal truth value). It is never quite clear if Atlantis is primarily intended as myth, history, or prophecy, but the last of these approaches should not be underrated. It would have been clear to any truly discerning mind (as was Plato's), that the cross fertilization, in history, of the discursive and symbolic modes of Logos, each having been autonomously developed to a high degree, was bound, at some point or another, to produce something like the world-spanning “Atlantean civilization”. Guenon was, in spite of himself, the shaykh al-akbar of the awliya ash-shaytan, the true awliya ash-shaytan, not the psychically reductive formulation of them that he presents in his own writing [2]. His work is the seed of a coming Atlantean civilization. He perfected the cosmopolitan vessel of universality, or at least laid the groundwork for this endeavor, namely, the endeavor of expressing symbolic and intellective universality in the form of a science of general concepts. Guenonian perennialism is perennialism par excellence. It is not just any kind of perennialist thought, but the attempt at rendering a generic meta-language for discussing Tradition and metaphysics, not for the purpose of scholarly survey, but in such a way as to facilitate an efficacious contact with the content of Tradition—and what is decisive is that this is actually executed skillfully (even in the tactillective sense).

On political and practical grounds, within the present social context, neither Guenon's cosmopolitanism nor Heidegger's provincialism can be realized without severe compromises, however. Guenon's perennialism can only become the preserve of a social elite, within capitalist civilization (see: King Charles), since no other civilization presently exists. It becomes a thing discussed at exclusive ecumenical conferences (see: Seyyed Hossein Nasr) among those with the wealth and leisure for such “hobbies”. Heidegger's provincialism, in turn, within the present capitalist context, can only become an understanding of being which is enforced upon the masses, while an elite caste of “guardians of the ethnos” sacrifice their “authentic being” to a cosmopolitan mode of existence (see: Schutzstaffel)(—this is a topic which I plan on addressing in greater depth elsewhere)—mirror images of of a broken Tradition and the sundering of intellection. Only Promethean socialism can unite the two intellects within an integral (or, better yet, integralizing) civilization, a civilization of scientific reason wedded to the Promethean audacity which steals fire from heaven.

1: That is, the myth of Atlantis prefigures scientific universality, which is at the same time cosmopolitan universality, that is, the intersection of generality of concepts and universality of intelligibles.

2: Briefly, in Guenon's writings the awliya ash-shaytan (or the “anti-tradition”, as he usually calls it), effect a substitution between intellectuality (= spirituality = nous) and psychicality. If, however, we identify “Shaytan” with Prometheus, the thief of heavenly fire, then it is not the exclusion of intellect that would characterize such an “anti-tradition”, but the seizure of intellect as a technology at the disposal of the rational and modern subject. This is what Guenon's writing unwittingly facilitates, on the side of active intellect, as expressed above. Indeed, in that respect, characterizing this tendency as a mere “anti-tradition” seems insufficient. It is something more like a neo-tradition, a post-tradition, a hyper-tradition—a sacreligion. Double entendre—from “sacrilege”, the stealing (“legere”) of sacred (“sacri—”) things, and the binding (“religio”) of the sacred toward human ends.

*

“Dasein plunges out of itself, into the groundlessness and nothingness of inauthentic everydayness”

(171-172)

That everydayness is somehow necessarily “groundless” is a faulty supposition [1]. When Dasein's environment (including social mores and the like, e.g. adab) is constructed intelligibly (i.e. symbolically), everydayness itself “defaults” to a grounded and “meaningful” mode of being. The groundlessness of the everyday is a result of the lack of integrality in the intelligible constitution of the social and political environment or, what is the same, the preponderance of transcendental factors in the structuring of the modern environment (as opposed to the pervasiveness of transcendent influences). Put yet another way, the present environment is not structured skillfully, that is, tactillectively. This present situation does not represent the normative or eminent ontology of Dasein, the default conditions of ontological inquiry into Dasein, but specific historical and social conditions which necessarily modify the nature of that inquiry, biasing it in a caprigenetic direction, if not in that of an outright objective presence. Thus, Heidegger's inquiry has an unacknowledged “historical bias”. It takes a certain species of everydayness as the exemplar of everydayness par excellence (if not the only species of everydayness).

1: Indeed, the caprigenus Dasein, whether authentic or inauthentic, is always caught up between groundedness and groundlessness—authentic Dasein is always “resolutely” trying to ground itself in its own fate, and in that very gesture proves its groundlessness. On the other hand, inauthentic Dasein, which is carried along inconspicuously in the They—the modern They, particularly—may, by virtue of the manner in which the social space is constituted at present, participate in some degree of groundlessness, but, comparatively speaking, inauthentic Dasein is more grounded than authentic Dasein (so long as we have the caprigenus Dasein in mind), and this by virtue of the inconspicuous intelligibility that characterizes Dasein qua Dasein, its most basic, immediate and “metaphysically concrete” (grounded) character.

*

“We have not decided whether human being is 'drowned in sin', in the status corruptionis, or whether it walks in the status integritatis, or finds itself in an interim stage, the status gratiae”

(173)

The practical limit of Heideggerianism is the “status gratiae”. It cannot effect a full integrality in the world (“status integritatis”) because its relation to being is fundamentally nostalgic and pessimistic. It either pines for a lost state of being (the “first ontopolitanism”) or else “stands resolutely”, true merely to itself (that is, authentically rather than archeimitically), in an environment that, at a basic level, is felt to be “ontologically foreign” (namely, the environment of modernity). The most it can hope for are moments of “ontological grace” that, for a time, allow it to experience a brief window of uninhibited authenticity, or else it can seek out some isolated space where such grace is more “ready-to-hand” (e.g. through a retreat into rural solitude). Indeed, Heidegger himself admits that “the They” is not an objectively present entity, but a manner of being that occurs “within” Dasein. If, then, this “They” is experienced as a site of inauthenticity that must be overcome, how can Dasein attain an integral being? “The They” are not going anywhere anytime soon. “The They”, too, must be sanctified. That is, Dasein requires a fully integral sociality, and the fabric of sociality gets its warp and its woof from the symbolic structure of class relations, from the “material” situation. Because the capitalist class is, intrinsically, a mediating class, integrality cannot be established under their rule. Communism is the precondition of Dasein's social integrality under the social and technological conditions of modernity.

*

“Ontological unity of existentiality and facticity”

(175)

This is about as good as a “technical definition” as one could ask for of passive intellection as a mode of being. “Facticity” can also be connected with tactillection, since it is a skillful handling of and integration with the factical situation, such that Dasein's being-in-the-world retains its unbroken and inconspicuous flow, which constitutes tactillection. A corresponding definition of active intellection might run something like “the gnosiological unity of essentiality and concentrillection—that is, the mode of being (or, in this case, primarily of knowing) in which the what-it-is-ness of that-which-is retains its constitution integrally and uninterruptedly in the concentrated absorption of knowledge [1]. The compound “gnosio-logical” is particularly apt because the “logos” here also suggests a symbolic mediation, and “unity” further highlights the fact that symbol is, ultimately, not really distinct from symbolized. With respect to the term onto-logical, we might similarly note the significance of “discourse” in Heidegger's account, as well as the basically symbolic structure of Dasein's being-in-the-world.

1: Essence is “always already” essential, but it is not always so concentrillectedly. In concentrillection, essence is realized in its essentiality, its “ownmost” (in an archeimitic sense) essentiality.

*

“Can the being of Dasein be delineated in a unified way so that in terms of it the essential equiprimordiality of the structures pointed out becomes intelligible, together with the existential possibilities which belong to it?”

(176)

The most obvious way to fulfill the conditions in the first part of this question is through the use of symbols. It is only a symbol that can “instantaneously” evoke the whole structure of that which is “equiprimordially partitioned” in a fully intelligible way. As for the second part of this question, an enumeration of possibilities obviously requires a metaphysics. A certain reservation is also necessary here, in as much as Heidegger has needlessly limited himself to existential possibilities, whereas a complete metaphysics must also refer to non-existent possibilities. If such a complete metaphysics is possible from the standpoint of active intellect, then it mus also be possible from the standpoint of passive intellect. The question then is—at what point, in what way, and through what means does passive intellect “make contact” with such non-existent possibilities? This has been touched on in the last installment of notes. There may be more to say on this later on.

*

“The absorption of Dasein in the They and in the 'world' taken care of reveals something like a flight of Dasein from itself as an authentic potentiality for being itself”

(178)

Likewise, Dasein's pursuit of merely being itself, in the present historical and “material” situation, is a flight from the broader task that makes a fully integral being possible for Dasein—and such an integral being, needless to say, is not found within the limits of modernity “taken at face value”, nor in a retreat, impossible to accomplish, to antique tradition. In order to merely be itself, Dasein must run away from this task, as Heidegger did when he fled to the petty authenticity of his Black Forest retreat, or, as he attempted with more sincerity, when he adopted the Nazi ideology—although this latter consists merely in a large scale enforcement of the former [1]. The realization of a fully integral being, for Dasein, requires an integration of the They which, in turn, requires a broader socio-political infrastructure. Such an infrastructure would need to be structured intelligibly, and in such a fashion that “They-ness” itself is seamlessly converted into integrative sociality. Thus, because a certain form of integral sociality—namely, communism—is materially necessary but politically excluded, Dasein's task, in the present, is necessarily revolutionary. A fully integral “authenticity” (or what is rather an archeimicity) is only possible to Dasein to the extent that this task succeeds. Moreover, socially speaking, such “social archeimicity” can only belong, in the most eminent way, to a member of the working class. The other classes, participate in social archeimicity to the extent that they defer to this class' rule—that is, they have a second hand social archeimicity to the degree that they are ritually oriented about the social center. Needless to say, under the present socio-political arrangements, there is no openly established center. One could therefore say that Dasein's flight toward mere authenticity is a flight from the task of reestablishing an integral social center, a flight from archeimicity as well as from that which would practically realize it in the present historical situation.

1: The resolute decision to retreat (to that metaphorical “Black Forest”), and submit to fate, incarnated in the upper echelons of the Nazi party and the Schutzsaffel, and the “experience” of the retreat, the volkisch life within destined boundaries, incarnated in the “racially pure” majority—the psychological and ontological split of the caprigenus Dasein repeated at the social scale. The upper echelons of the Nazi party made the decision of “retreat” on behalf of the racial majority. That “Black Forest” could, in such a case, just as well be a “futuristic” cityscape. It is a lived simulacrum of life for the “racially pure”, a theater of volk-kitsch experience managed by the stagehands of the Nazi party—it is auto-voyeurism, auto-tourism, auto-eroticism, facilitated by cosmopolitan construction projects like the auto-bahn.

*

“[Through anxiety], the world in its worldliness is all that obtrudes itself”

(181)

That it can obtrude itself in this way, at all, implies a loss or absence of integrality. The world has split itself, doubled itself—it is both that which I am in, and that which obtrudes itself before me. Thus, anxiety requires a loss of integral being as its precondition (or, in a sense, a displacement of integrality, enclosing it within a surveyable sheep pen). From whence this loss? That must be investigated. The aforementioned substitution of Theyness for integral sociality factors into this, but we should be careful not to fall into the trap of supposing that integral sociality on its own, abolishes all the “fractures” in being. In the broadest sense, a really completed integrality requires something like a “metaphysical realization” (in our just established terms, an “archeimitic realization”). Nevertheless, integral sociality will preserve a relatively adequate integral way of being for most “Daseins” (but most eminently not for a category of persons we might call the “satyrs”—but more on this later), and, in any case, it will serve as a support for further “metaphysical realization” (in the case of those who choose to pursue it). One can further surmise that the world becomes ever more obtrusive to the extent that a lack of social integrality predominates. If no center maintains the world in a unity, it becomes split and continually splits itself. Thus, anxiety is not a passage leading to Dasein's possible authenticity (or, rather, leading to its archeimicity), in a fully integral sense [1], but only in a fractured sense, revealing only the possibility of an “authentic escape” into the Black Forest of pseudo-provinciality. Anxiety shows us the possibility of being in a split-world, of barricading ourselves on one side of this divide (barricading ourselves “authentically”). Unless, of course, we take upon ourselves the revolutionary social task of repairing this divide at the “material” level, the task of rendering social integrality possible within the conditions of social and technological modernity. Anxiety, in other words, is a symptom not of worldliness “as such”, but of fractured wordliness, of a being-in-the-world which has been “split in advance” at the “material” level.

Moreover, in a somewhat paradoxical fashion, a total integrality in the context of modern technologies and the present social form, is an integralizing sociality, not a merely integrated sociality. This is a sociality which expresses at its own scale the split which has occurred within primordial intellect, and which has reached the acme of its development in modernity—philosophically, in the apotheosis of transcendental subjectivity through Kant, and the subsequent expression of radically isolated intellects through Heidegger and Guenon. The political institution of proletarian dictatorship brings the intellects back together, but not as simple identity, a reunion identical to their condition at the first, but directed and seized by the heroic embrace of the Promethean subject—symbolically, the winged serpent and, mythologically, the raising of Atlantis. The rupturing power of rationality is retained as the stimulus of integrality, and the integrality of the intellects as the world-forming power of the rational subject.

1: That is, archeimicity is integral authenticity, and authenticity, in its privative sense, is a shadow or echo of archeimicity.

*

“Anxiety individuates Dasein to its ownmost being-in-the-world...Anxiety discloses Dasein as being-possible, and indeed as what, solely from itself, can be individualized in individuation...Anxiety individualizes and thus discloses Dasein as 'solus ipse'...existential 'solipsism'...In anxiety one has an uncanny feeling...Uncanniness means...not being at home...Anxiety...fetches Dasein back out of its entangled absorption in the world” (182)

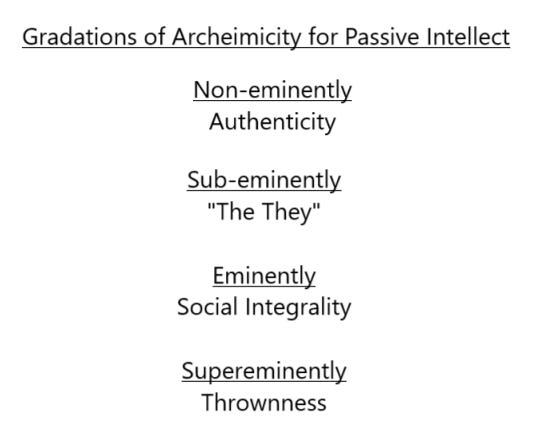

Individuation, like objective presence, is an expression of the transcendental nothing, a “species” of nothing [1]. It is, indeed, from any strictly causal standpoint, quite impossible to say whether anxiety individuates Dasein or whether individuation (or that nothing from which it is both distinct and indistinct) is the origin of anxiety. To reduce anxiety to a psychological phenomenon is perhaps a bit reductive, but to treat of it exclusively in ontological terms would be misleading. It is something like a psycho-ontological phenomenon—that is, of a mixed character, like the caprigenus Dasein whom it “afflicts”. Indeed, anxiety is nothing other than an acute psychological expression of the irrationality of reason in its sharp divorce from intellect—it is the irrational and silent scream of reason, its terror at the unreason it discovers in itself. That is to say, it is a psychological expression of the ontological structure of caprigenetic Dasein. In a word, it is authenticity—mere authenticity, erected as a barricade against archeimicity, universality, social integrality. The caprigenus Dasein generally (in its everydayness) encounters universality (social integrality etc) merely as “the They” (das Man), an echo of universality, as it were. “The They” already expresses archeimicity—non-intensively, “sub-eminently” (in the sense of a lesser degree of eminence), as it were. A kind of gradation can be established:

As expressed in the previous installment of notes, possibility for Dasein (passive intellect), is to be located, supereminently, on the side of “act”, in the plenary non-being of thrownness, of which anxiety (uncanniness, objective presence etc) is an inferior expression. Thus, we could say that anxiety, as a psycho-ontological phenomenon, is, at best, a semblance of that which discloses possibility supereminently for Dasein, namely, thrownness in its most plenary and intensive expression. Once again, Heidegger's caprigenetic conception of Dasein is holding him back from grasping Dasein as it really is, both as it is eminently and supereminently. Indeed, more than this, one could further distinguish between a conceptual semblance and an essential semblance. Anxiety, here, is a mere conceptual semblance of Dasein in its supereminent possibility. It is inconspicuous being-in-the-world which possesses an essential semblance, a genuine image of Dasein in its pure possibility. It is, after all, Dasein's being-in-the-world which is tactillectively constituted, whereas objective presence consists in the interruption of tactillection—but on the “other side” of this interruption is the condition of thrownness, in its purity, wherein tactillective flow is unconquerable. There is, therefore, an intelligible semblance between Dasein's inconspicuous being-in-the-world, its everyday dealings in “the They”, and its supereminent condition of “pure thrownness”[2]. Moreover, the difference between the eminent expression of Dasein's being-in-the-world and its “sub-eminent” expression, as given above, is merely one of degree, a matter of intensity. They are essentially the same. It is through supereminence that one crosses over, beyond essence, beyond intelligibility, beyond being. Between this supereminent condition and the transcendental anxiousness of caprigenetic Dasein there is a “dissimilar similarity” (see the third part of my notes on the Prolegomena), and a generic ambiguity of a special kind—that is, the generic ambiguity between that which is the same as generic ambiguity itself, for all intents and purposes, namely, transcendentality, and that which transcends being and intelligibility. Again, this is what has been referred to elsewhere as the analogy between the “two nights”. Here, I also call it a “conceptual semblance”. Another crucial point, clearly implied in the diagram above and by the discussion thus far, is that even authenticity is, basically, an expression of archeimicty—a barricade against it, yes, but one that expresses that which it spurns, in spite of itself. I-saying (automorphosis) is a shadow of archeimicity. What automorphosis does succeed in postponing is not archeimicity as such, but eimimorphosis. It is an effective barrier only against subsumption into, or realization of, that which is “always already” the case.

Anxiety is the fear of the loss of authenticity, which is to say, the fear of archeimicity. Thus, one can characterize it both as an obstacle to archeimicity and as the passage leading to it (or the sign which indicates it). Anxiety is the urgency of I-saying—it says “what will you do without I—you will flop around like a fish out of water. I will safeguard you. I am equipped to handle every situation you come across”. You-saying is the defensive barricade of I-saying. It is a hostage situation and a bluff, a gun without bullets. “Solus ipse” is always already divided against itself—it is always you and I. Above all, it is nobody at all. Solipsism is a gallery of masks without faces, an extremely crowded situation. Indeed, what could be more “uncanny” than this? Uncanniness is the flavor of worldliness for caprigenetic Dasein, for that Dasein for whom merely being Dasein is no longer sufficient. It needs authenticity, as well, and the price of authenticity is anxiety and uncanniness.

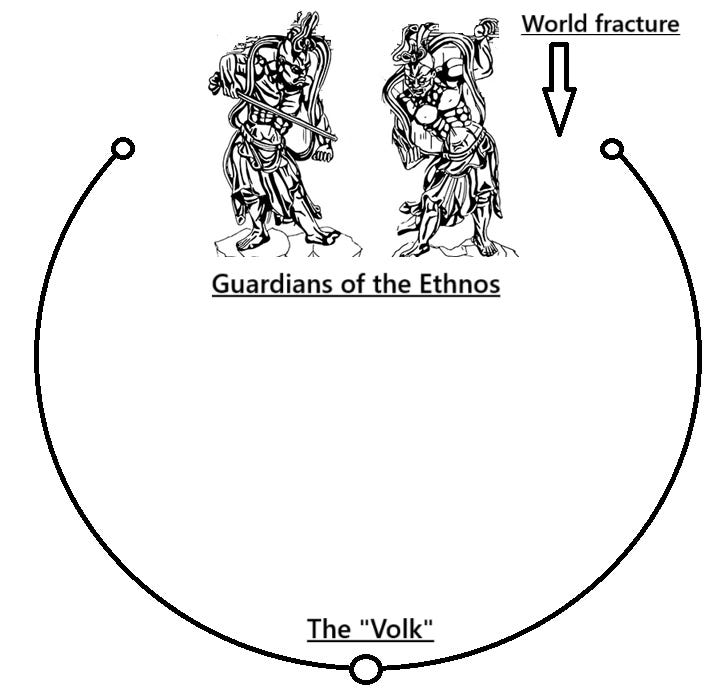

Heidegger, then, considers anxiety to be a “fundamental mode of being-in-the-world” for Dasein. To the extent that such anxiety can reveal fundamental fractures in the Dasein's world which spur one toward an “archeimitic realization”, it is hard to dispute this contention. Consider, for instance, the anxiety that launched al-Ghazali on his path to realization, his transition from the disputation of philosophers to the contemplative rigor of tasawwuf. In that sense, it is “fundamental”. It is fundamental to Dasein attuned to the “screaming silence” of reason, Dasein confronted by the uncanniness of its own I-saying. However, for Heidegger, this constitutes a revelation of “world in its worldliness”, rather than world in its fractured character. Such an approach can only terminate in a sort of embarrassing and limp resignation (from whence Nazism, then? Nazism is that militant cosmopolitanism ranging abroad that safeguards the security of spiritual laziness “at home”). Neither the task of repairing these fractures (“archeimitic realization” or restoration of social integrality) nor the the possibility of seizing upon the fracturing power as a technology (Prometheanism) can reveal themselves to this closed mindset. Nazism, then, as I have suggested in my essay on the political spectrum, seeks to freeze the current world configuration, i.e. the current configuration of fractures in the world—it naturalizes and mythologizes this arrangement, with the “guardians of the ethnos” standing sentinel on one side of the divide, and the “volk” securely resting in the other, at the comfortable middle ground of the spectrum of oppositions.

1: Individuation is that nothing which marks off the individual from the species. It is precisely a nothing because the individual remains of the species in spite of the incision. It is cut off and not cut off. It is nothing at all which marks it apart, and therefore allows it to retain its togetherness.

2: It is worth noting that Heidegger does not use “thrownness” precisely as I do. He does not mean a condition that Dasein sometimes occupies and at other times does not, but indicates only a general feature of Dasein's manner of being. Our usages here do differ, but they are not unrelated. One could say that “pure thrownness”, as I use it here, is thrownness realized, a transcendent repose in passively intellected non-being. Put another way, Heidegger speaks of thrownness as the general “flavor” of Dasein's being. I am indicating the possibility of fully tasting it, imbibing it—drowning in it.

*

“Being-in was then made more concretely visible through the everyday publicness of the They which brings tranquilized self-assurance”

(182)

There is a definite tension in Heidegger between a “provincial authenticity” (fate) and a contempt or almost extreme “skepticism” toward the same. This tension is not a tension between two “alternatives” placed side by side, but the tension between a certain state of being and its origins. “The They”, for Heidegger, constitutes Dasein's initial mode of being, and only from out of it or through it is something like “authenticity” possible. Thus, only one who belongs to a “public world” can attain authenticity. Translated into reactionary political language: only a man of the volk can become a “guardian of the ethnos”. Authenticity ferrets out the “destiny” of “the They”, and resolutely seizes upon it.

*

“Tranquilized familiar being-in-the-world is a mode of the uncanniness of Dasiein”

(183)

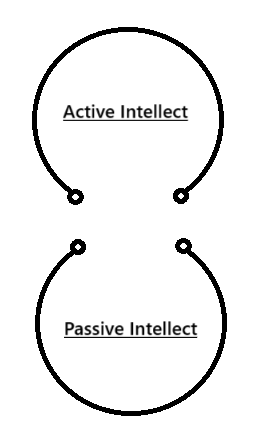

In other words, tranquility (found in the “the They”, primarily) is only sought because of “uncanniness”, in order to flee this “uncanniness” (or anxiety). Here, Heidegger is attempting to subsume inconspicuous being in the They into authenticity, as if to say that the former is merely an inferior expression of the latter—hence, why settle for the inferior and “inauthentic” expression? It is fear that prevents this. Hence, the one who squarely faces uncanniness is a kind of “moral hero”. This Heideggerian framing of the situation is to be rejected since, in fact, he misses the distinction between caprigenetic Dasein and Dasein qua Dasein. Anxiety (uncanniness, etc) is a property of the fracturing of the world, not of “world as such”. One who primarily lives within world, in an intelligible way, has not necessarily encountered a fracture from which to flee [1]. There is a sense in which living within the intelligibility of some fractured portion of world is sufficient, an icon of the world in its full integrality. At the most basic level, the simplest and most primordial of fractures is that which occurs for primordial intellection through the intervention of the nothing, and the most primordial of “portions” of the fractured world in which one might dwell, therefore, are none other than the intellects themselves. Thus, the most basic world fracture looks something like this, if one were to express it as a figure—a circle divided into two broke circles (“horseshoes”), a kind of suspended cellular mitosis:

Is one, then, who lives exclusively within one such portion, scrupulously avoiding the points of fracture (whether deliberately, or simply through sheer obliviousness), simply fleeing? The task of transcending this fracture (“archeimitic realization”) has no relevance for most, and the task of repairing it (social revolution) is a Herculean one—neither of these tasks, by the way, are recognized by Heidegger. The Heideggerian task of merely “facing” this anxiety, that is, the task of “fateful authenticity”, is thankless, and frankly rather pointless. Is the one who is content with his portion of intelligibility really just “fleeing”? Only if we choose to frame uncanniness as the primordial phenomenon here, but that is ontologically absurd (the thinker like Heidegger who has hit upon the experience of uncanniness tends to believe that they have, at last, come face to face with the “real thing”—naturally, only a “moral hero” could be equal to this hard “truth”). In a sense, then, what Heidegger considers mere “fleeing” is a genuine solution to the problem of the “world-fracture”. It discovers a portion of this world in which intelligibility can still reside [2]. Perhaps, “fleeing into the “idle talk” of modernity is no adequate substitute for a fully intelligible and integral dwelling, but—and this is the crucial point—Heidegger's proposal of “facing up” to such anxiety is a pseudo-solution, a solution which itself “flees”, as it were, from the Herculean task of social revolution, or from the “scientific” and ascetical rigors of “archeimitic realization”.

1: Theoretically speaking, that is. Practically speaking, in the context of modernity especially, it is exceedingly unlikely to not encounter such a fracture, to say the least. Hardly anyone slumbers in “the They” that deeply. Nevertheless, from a theoretical standpoint, it is a mischaracterization of Dasein qua Dasein to attribute to it things which are characteristic of it only under certain “special” conditions and which, in terms of ontological structure, are merely caprigenetic.

2: Is this not what Heidegger has in mind in connection with fate? Yes and no. Fate is faced resolutely and authentically, and it is precisely this manner of submitting to fate which is characteristic of the caprigenus Dasein, rather than Dasein qua Dasein. Dasein qua Dasein simply is its own fate and requires no resolution or choice. It is its fate inconspicuously, whether it finds its fate in “the They” (horror of horrors!), or it finds it in an integral social environment. Heidegger desires the drama and moral heroism of a choice. This resolution, in paradoxical fashion, makes the “natural born son” of his nation, the “volkish” ideal, into a tourist of his own people. Volkishness is made into tourism, by virtue of attempting to be its opposite—even when it has every right to assert itself as its opposite, even when one's “volkishness” is fully credentialed and certified. It is the most perverse kind of tourism, a kind of union between masturbation and incest. The provinciality of the “first ontopolitanism” is a species approaching extinction, whether we like it or not. Attempting to re-engineer it into existence is product of the perverse will of all such reactionaries—the attempt to preserve the naturalness of nature, as though it needed any such assistance.